Flotillas of stand-up paddleboarders, clusters of inner tubes, beach parties, sunbathers, children splashing about with plastic toys, dogs playing fetch in the river — these have become common sights during summer months at the North Star Nature Preserve.

It is only in the past few years that such explosive popularity has visited these public lands several miles east of Aspen, where an inviting channel of meandering river has become an Aspen summer playground.

Much of the new popularity, says John Armstrong, ranger for Pitkin County Open Space and Trails, is due to a surge in stand-up paddleboards (SUPs), a recent trend that has made North Star a water-sports mecca.

Most paddleboarders have little ecological impact on the Stillwater section of the Roaring Fork, Armstrong says, but as numbers of boarders have increased, the once quiet atmosphere has disappeared.

“The real damage is to the experience. If you’re looking for a tranquil, solitary experience, now we get a lot of people, some of them whooping it up,” Armstrong said. “To those who knew North Star in the past, that’s gone now. The quality of the experience is different.”

Gary Tennenbaum, assistant director of stewardship and trails for the Open Space agency, agrees.

“It’s not unusual to see 100 or more individuals floating the river on any given day in the summer,” he said.

Neighbors and Nature

According to Andre Wille, an Aspen High School biology teacher whose family home has been on the Stillwater section of the Roaring Fork River for 35 years, the recent surge in river recreation at North Star has been dramatic.

“Popularity has triggered some ecological effects because animals tend to hide when people are present, but floaters have the potential to leave no trace, and that’s a good way to see North Star,” Wille said. “Some education is needed to sensitize the younger generation because there have been some abuses. Still, what better way than floating the river to raise awareness and appreciation for nature?”

While paddleboarders are pushing the popularity of North Star, Wille says they are relatively innocuous.

“Inner tubes are the biggest impact because there’s beer drinking,” he said. “You can’t take beer on a (stand-up paddleboard), and those users tend to be conscious of their impacts.

“We have had a house on the river there for 35 years, and while I don’t like a ton of people coming down the river, I can’t blame them unless they have unleashed dogs — that’s not cool. North Star is right on the urban interface with Aspen.”

Neighbor Edgar Boyles, whose home is on a bend of the river just downstream from the put-in, describes a more serious impact.

“When they come around that bend, they hit a little whitewater, and the girls get splashed, and they scream like it’s a 1964 Beatles concert,” he said. “After the first wave, you hear, ‘This is f—ing awesome!’”

Boyles and his family have enjoyed a quiet riverfront location since the 1970s, but sudden popularity of the river has changed that.

“The last thing I want is conflict. The first thing I’d like is to be left alone,” Boyles said. “It’s really a moral issue: Do we have reverence for this place? Do we have quiet? Or do we drag the 12-pack behind in a net and make a lot of noise? There’s a place for that — it’s called Water World.”

Hordes and Herons

Is North Star being loved to death? A public survey and biological evaluation by Open Space and Trails will ask that question this fall. At issue will be whether human visitation is in potential conflict with the plant and animal communities that depend on the preserve for survival.

In a recent report, Tennenbaum reminded the public of that mission: “Our continuing goal is to offer opportunities for limited public recreational use in this special river corridor while managing it to minimize impacts to the ecological values of the properties.”

Of particular sensitivity at North Star is a great blue heron colony, of which there are only 63 in Colorado. The North Star colony is thought to be one of a few occurring above 8,000 feet.

The management plan identifies the North Star great blue heron colony as “unique and ecologically significant … with a recommended minimum 200-meter buffer zone from the periphery of colonies in which no human activity should take place during courtship and nesting seasons. Because colonies may move every few years, management plans should encompass entire river systems.”

The management plan also addresses a far less visible – and more protected – species than herons: “If boreal toads are federally listed as endangered or threatened, then we will be bound by law to increase the protective status of North Star.”

A petition for that designation was filed in 2012 with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

A River Runs Through It

Paddling North Star offers a mellow journey over limpid waters through a lush riparian ecosystem.

“Less than 1 percent of the land in Colorado is riparian, but over 60 percent of vertebrates are dependent on riparian ecosystems, and approximately 85 percent require riparian habitat for some aspect of their life history,” the management plan states.

Trout swim below, birds fly above, and various mammals populate the land. Kayaks and canoes have plied the waters for decades, many receiving paddling instruction from the Aspen Kayak Academy.

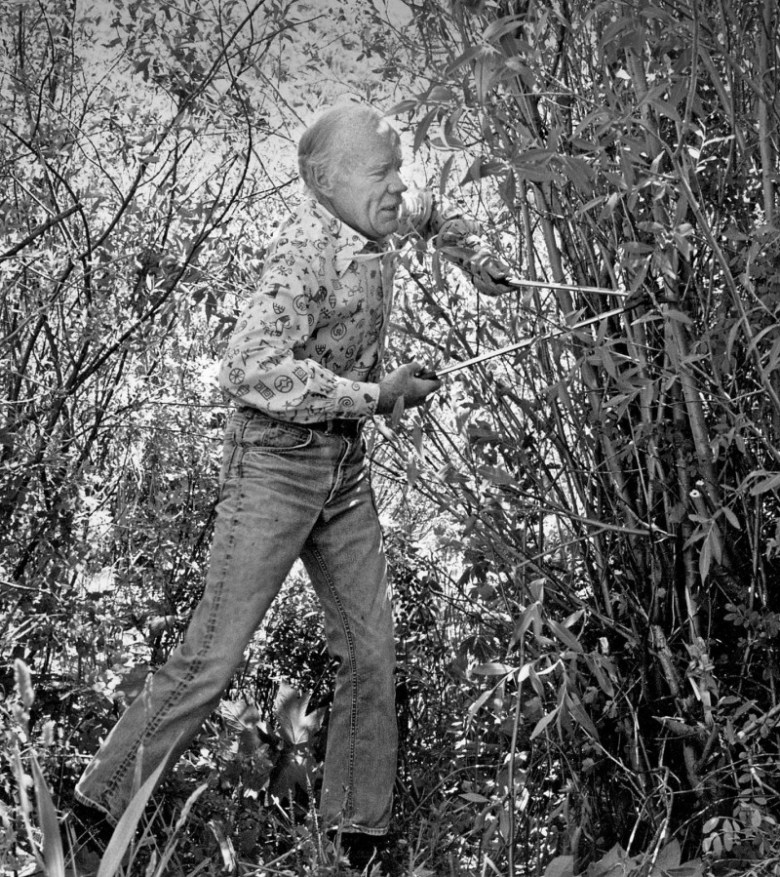

Charlie MacArthur, who took over the academy from founder Kirk Baker, says he was among the first to introduce stand-up paddleboards to the Aspen area.

“I was copying the Hawaiians and got hooked,” he said, having added stand-up paddleboards to the academy in 2007.

“North Star is a fantastic experience,” MacArthur said, though litter has become an issue. “I’ve seen a lot more trash, and I pick it up. This year there seemed to be a little less trash, so people are picking up after themselves. So far, I’ve seen no other impacts.”

Commercial stand-up-paddleboard rentals have boomed with the recent trend, says Ed Garland, an owner of Aspen Bike Rentals, next door to the Butcher Block in downtown Aspen, which began renting stand-up paddleboards three years ago.

“It’s just another activity people can do to have fun, and North Star is where most people go,” he said.

Stand-up paddleboards rent for about $50 per day, and paddlers provide their own transportation to the put-in on Wildwood Lane. That put-in, the only control point for river access, is managed by the U.S. Forest Service, which currently has no restrictions on numbers.

“It’s only three and a half miles from town, and the water is calm, slow-moving and beautiful,” Garland said. “Everyone loves paddling the preserve, and our rentals have grown every year. Our customers love it; they’re very happy with the experience.”

“Stillwater is the most popular place to paddle,” said Kelsey Rossi, of Four Mountain Sports in Aspen, which rents stand-up paddleboards. “It’s one of the only sections of moving water they can get to easily.”

On big summer weekends, Boyles says his subdivision road sees traffic and parking conflicts.

“It’s basically a one-lane road, and on numerous days there are so many parked cars that they can’t get the Wildwood school bus out. That could become an emergency issue, and nobody wants to step into that. River users should be informed that there are impacts on both nature and community.”

“The big thing is education,” MacArthur said. “Paddlers need to be aware of private property because they’re paddling through some backyards. That means being courteous, not being loud. I’ve seen a lot of boom boxes and drinking, and I say it’s a preserve and to tune it down. The main complaint is rowdiness, loudness, drinking and noise.”

North Star Discovered

Armstrong says North Star was considered underutilized until a recent summer drought put it on the map.

“Four or five years ago, I began to see a change in the number and types of users,” he said. “It used to be meditative bird-watchers and not a lot of people. Then came a drought when we had almost no water at Herron Park in Aspen, and the kids’ wading area went dry. That’s where moms and kids go to splash around.

“Word got out that there’s a beach at North Star, and it just exploded. Simultaneously, the stand-up paddleboard came on line, and word-of-mouth did the rest.”

Tapping the recreational trend at North Star, Corby Anderson, host of “On the Hill,” a regular video feature of The Aspen Times’ online version, featured North Star in August.

In his segment titled “Putting the Ahhh in Aspen at North Star Preserve,” Anderson acknowledged the significance of natural resources but concluded that recreation has become the focal point of the preserve.

“North Star’s a playground for … hikers, dog walkers, paddleboarders,” he reported. Then, swinging his camera to three bikini-clad young women poised to leap from a bridge into the Roaring Fork River at North Star, the final sentiment was, “Yee-ha!”

North Star’s Founding Values

In respect for wildlife, access to North Star Preserve is strictly controlled. Hiking trails from Highway 82 have been routed to avoid heron rookery sites. Still, the Roaring Fork River flows near some rookeries, allowing floaters an up-close and personal view of these large and imposing birds, many of which roost in evergreens, not their traditional cottonwoods.

“What we feared was egressing the river at random places,” Armstrong said. “We’re not seeing people abusing that. We’re not finding trail braiding. People are respecting the gate system.”

“What’s not covered,” Boyles said, “is when people blow their tubes and have to hike out back to their SUVs through private property and sensitive areas.”

Wille, who heads Pitkin County Healthy Rivers, says today’s overall impacts are relatively small compared with willow eradication during North Star’s ranching phase. Healthy Rivers hosted a floating tour of North Star in August where Wille pointed out destabilized riverbanks prone to collapse because of a lack of willows.

“The delicate riparian zone was cleared of willows, and some rechanneling may have been done,” he said. “In many areas the riparian zone is open, where it naturally would be grown up in willows. Willows are a bonding plant. They also provide protective screening for deer and elk, plus bird habitat.”

Coordinating with Open Space and Trails, Healthy Rivers is planning to enlarge willow populations.

“Restoration takes time,” Wille said, “but 10 years later you can see the benefits. We have funds to apply to that, so that’s our goal.”

Balancing Nature and Recreation

Floating Stillwater may seem innocuous, but future growth looms because of what Armstrong refers to as the “huge social thing” among floaters.

“The people there are now very different, but there is undeniable joy,” Armstrong said. “You see kids with plastic toys, and it’s a little like Coney Island, but would you pull the plug on that? It’s the people’s land and resource, and it’s our job to balance that with resource protection.”

While the ecological sensitivity of North Star is documented, so is human use, which the current survey will measure.

“Nobody has jurisdiction over the water unless you get out of your boat and step on the river bottom,” Armstrong said. “Otherwise, the water is public.”

The management plan acknowledges public use: “The preserve is an important cultural asset to the citizens of the Roaring Fork Valley that can further ecological awareness and understanding,” the plan says. “As such, one of the most important goals of this plan is to achieve a balance between North Star as a nature preserve and as a cultural resource.”

From Cattle Ranch to Recreation

The North Star Nature Preserve was once a historic ranch that raised cows and grew hay. The preserve is actually three neighboring properties — the North Star Nature Preserve, the James H. Smith Open Space and a parcel owned by the Aspen Center for Environmental Studies — totaling 309 acres.

Most of the preserve was carved from North Star Ranch, which James Smith acquired in 1949 from a notorious Aspen bootlegger. Smith, an aspiring rancher who served as undersecretary of the Navy Air, named the Polaris Missile System for his beloved North Star Ranch.

In the mid-1960s, the Aspen Area General Plan allowed construction of as many as 1,500 houses at North Star Ranch, plus some recreational and commercial development. This magnitude of development was rejected by Smith, and Aspen residents were alerted that the town’s eastern entrance risked losing its rural atmosphere.

In 1973, Smith submitted an application for a reduced 350 residences, which was denied by the Pitkin County commissioners, who the following year downzoned much of the county, including the eastern approach to Aspen.

North Star Ranch was rezoned to AF-1, which allowed development of as many as 36 units. This led to conversations between Smith and members of the Pitkin County Parks Association concerning the possibility of converting part of the ranch to open space. The result was the selection of a 175-acre parcel within the ranch and an appraisal of that parcel in 1977.

The county Planning Department took the lead in the acquisition process with the application of a 50-50 matching grant of $575,000 from the Federal Land and Water Conservation Fund, administered through the Colorado Division of Parks and Recreation for the Federal Bureau of Outdoor Recreation.

When it was learned that these funds would not be available in 1977, The Nature Conservancy, then headed by Aspenite Jon Mulford, was contacted. Mulford renegotiated the purchase price to include a gift valued at $275,000 from three generations of the Smith family.

In November 1977, The Nature Conservancy took title to 175 acres of North Star Ranch, which it transferred in December 1978 to Pitkin County, which began managing the property as a nature preserve — the first of its kind in the county.

Legacy of Conservation

The original North Star Management Plan focused on nature and its continued protection: “The conservation imperative at North Star is to preserve a mosaic of high-quality native ecological communities that support a high level of biological diversity.”

That became policy when Sydney Macy, one of the preserve’s chief conservation advocates, and then Colorado Field Office director for The Nature Conservancy, wrote a letter to the Pitkin County Planning and Zoning Commission on July 18, 1984:

“The intent of the acquisition, which is in keeping with The Nature Conservancy’s objective of preserving natural areas, was that North Star Ranch be managed as a natural area for scientific and educational purposes while still encouraging and allowing some passive recreation.”

Then County Planner Bill Kane, in a letter to the Colorado Division of Parks and Outdoor Recreation, wrote, “It is our contention that this land, if acquired, would present the prospect of an elk refuge in perpetuity.”

Morgan Smith, son of James Smith and former director of Agriculture for Colorado, specified the purpose of the family donation of $275,000 that secured the preserve: “This donation … was intended to keep the land in open space and for the purposes of wildlife. We never would have made the donation if there had been discussion of commercial usages. In addition, it was always our hope that this donation might serve as an example to others who are interested in preserving land and protecting wildlife.”

While James Smith cursed willows as his ranching nemesis, willows are recognized today as a valued plant, of which North Star nurtures five distinct species.

North Star also supports a high level of biological diversity, with 17 species of small mammals and at least 107 species of birds — more than 60 of which are likely to breed at North Star. There are 13 medium to large mammal species, including elk, coyotes, black bears, bobcats, one reptile species and three species of amphibian, including the boreal toad, a potentially endangered species.

The preserve harbors 10 distinct vegetational communities: mixed conifer forest, aspen forest, cottonwood riparian, willow riparian, oak-serviceberry shrubland, dry meadow, mesic hayfields, wet meadow, emergent sedge wetland and open water.

Aspen Journalism collaborated on this story with The Aspen Times, which published a version of it on Sept. 28, 2014.