ASPEN – Circa 1978, Waddill Catchings III, a frugal, understated mountain gentleman and Harvard graduate who had lived in the Little Annie basin since the early 1950s, and who had initially assembled 880 acres of mining claims there for a new ski area, showed up dressed head-to-toe in his 50s-vintage togs for a skiing summit on the basin’s western-facing slopes, to pass the torch to the new owner and next-gen enthusiast of the project, longtime Aspenite David Farny.

Known by all then as “Waddy,” the grand old caretaker of Little Annie basin southwest of the summit of Aspen Mountain, he wore baggy black ski pants, a faded anorak pullover and bat-wing goggles. Coupled with his wooden skis and poles with oversized leather baskets, “his gear was not part of a retro costume, but simply what he had,” reflected former Basalt city manager Bill Kane, who was there and worked then as a planner with Farny.

Bear in mind that the assembled group of next-phase think-tankers — who in 1978 had a flitting view of what was modern — respected the fact that Waddy had hiked and skinned up everywhere on seal skins and skied every nook of Little Annie basin and the east-facing side of Aspen Mountain. He knew the subtleties of the temperature patterns, changing snow and wind deposit locations like an Eskimo.

After moving out of his miner’s cabin in town in the early 1950s, about where today’s Meat and Cheese stands along East Hopkins Avenue (for you contemporary-challenged, opposite what was formerly La Cocina), Waddy moved up to Little Annie basin where he cut and delivered firewood. There, during those anything-goes times when overdone was a term applied to diner food, he set to work exploring and conceptualizing a new ski area three times the size of Aspen Mountain.

Pass the torch

To this end, in 1963, he and Fritz Benedict — the renowned 10th Mountain Division veteran and Frank-Lloyd-Wright-style Aspen architect who endured 113 straight days of combat in winter conditions in Italy during World War II — put together the Little Annie Development Corporation.

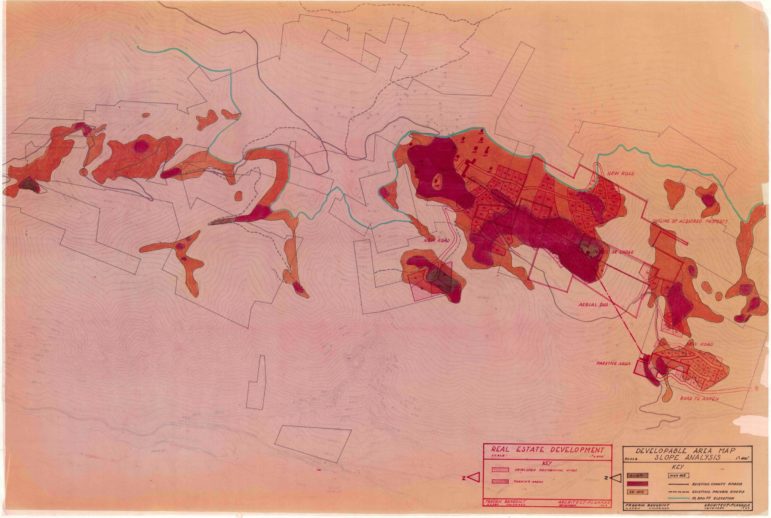

The actual rolled-up plan drawn by Benedict was discovered in the basement of Waddy’s old house in lower Little Annie basin by local planner and friend of the late Catchings, Glen Horn, who now owns the house. The architectural drawings, which detail terrain, snow exposure and slope degrees, ski lifts and developable lots, shed new light on Waddy’s one-time dream to build a Little Annie ski area and independent Tyrolean-style village there.

Though big development was not such a trigger phrase in the 1960s, his dream gradually lost traction. But Waddy was pleased to share his intimate knowledge of the basin and pass on his ski dream to Farny, whose community standing and talented family contributed much to Aspen in the 1960s and 1970s.

Yet Farny, in an almost Tesla-style gamble, risked everything and swung for the fences at every obstacle thrown his way, only to become — much to his and his family’s surprise — a lightning rod for the angry opposition in what was Aspen’s first major development battle that nearly split the freewheeling town in two, leaving many on both sides with the taste of bitterness.

Two grand plans

A 1994 recollected summation by former U.S. Forest Service district ranger Paul Hauk, who was pivotal in approving a number of Colorado ski areas during the 1950s and 1960s, says both Catchings’ and Farny’s attempts to build a Little Annie ski area met preliminary approval. But in both cases, myriad details needed to be ironed out, not the least of which was financing.

The major difference between the two plans was that Catchings’ proposed access would come up from Castle Creek on the western flank of Aspen Mountain, with an access parking lot at the base of Lime Creek, while Farny’s access rose from the Difficult Creek side east of Aspen Mountain, right out of town on Ute Avenue from a big gap between the Gant and Ute Cemetery. Both proffered innovative new gondola designs.

Hauk wrote that Catchings envisioned a 25-passenger “aerial bus” similar to one in Custer, S.D., to transport skiers and residents in and out of his self-contained village. Farny, in a more modern take, conceived of a “3.6-mile-long ‘dog-leg’ gondola” that angled up the Difficult Creek drainage to the top of Richmond Hill.

Early basin skiing

Sorting out the changing ownership of land parcels, mining claims, U.S. Forest Service terrain and squatters in the greater Little Annie area dating back is akin to monkeying with a Rubik’s cube. Yet there were roughly three historical snapshots of sizable control with a skiing interest, not including the swashbuckling mining era of the 1880s and 1890s when local Scandinavian miners got first tracks.

The first Little Annie ski area, started by the Highland Bavarian Corporation, offered 50-cent sleigh rides into the undeveloped basin from Aspen’s first ski lodge, the Highland Bavarian, at the intersection of Castle and Conundrum creeks below the west side of Aspen Mountain.

The corporation’s early design opened for business in December of 1936 and survived for a few years before the war put a damper on skiing development. They aimed to promote Aspen’s first ski area across from their lodge in Little Annie basin. For $7 a night at the lodge, skiers could climb up to the Annie ridge from the lower drop-off of the sleigh for a full run down.

The varied slopes in the basin led into a funneled run through gladed trees down to the lodge, past the Highland Tunnel — an on-and-off silver mining operation just across and uphill of the lodge. The more daring might venture over the top of Richmond Hill and ski down the mine-littered front of Aspen Mountain into town.

But developing skiing in Little Annie for HBC proved short-lived after Andre Roch and Dr. Gunther Langes, two renowned alpinists and ski experts recruited by the corporation, journeyed from Europe to assess the skiing potential there. Along with Olympic gold medalist and 1930s “jetsetter” Billy Fiske, a principal visionary in HBC, Roch and Langes set their sights on nearby Mount Hayden (see related story from Aspen Journalism, “Big mountain ski dream”) as the next international ski area. This ski dream, too, fizzled.

While the skiing right across from the lodge in Little Annie had its merits, Roch and Langes said the predominantly western exposure of the terrain delivered poor snow conditions. That exposure received too much sun, producing variable conditions, and would continue to be a concern in the two major iterations of the Little Annie ski area projects yet to come.

The next wave

Before visions of an entire ski area there, terrain in Little Annie and on the Difficult side was listed on trail signs at the top and bottom of Aspen Mountain as ski runs in 1950, though neither was maintained or patrolled.

The Feb. 20, 1958, Aspen Times advertised ski tours by the Aspen Ski Club in Little Annie basin, “conducted by experts.” Trips left the Sundeck at 11 a.m. some weekends, offering visitors “their choice of either Little Annie or Hurricane.” Tickets could be purchased at Ski Club headquarters in town for 50 cents for members and $1 for non-members. Dog sled tours were also available.

In the early 1960s before Catchings and Benedict completed their 1963 ski-area master plan that charted six chairlifts along with the aerial bus, they offered snow cat tours and a warming hut serving lunches on a deck with views of Mount Hayden. For this purpose their crew converted the Little Annie cabin that still stands on the left just as one arrives uphill into the open Annie basin, in a cluster of dwellings now known popularly as “the Village of the Dans.”

Up to this point Catchings and Benedict, supported by partners Robert Craig and Dick Wright, had been moving conceptualized lift placements, restaurant and hotel locations, building lots and new roads around in their heads like chess pieces. To chum up investors they needed regular ski tours.

Little Annie Corporation

The Oct. 26, 1962, Times announced the formation of the Little Annie Development Corporation with Waddill Catchings as president. Still, Waddy lived modestly and avoided trappings, as was the flannel-shirted norm during Aspen’s “good old days” when everyone lived in town in smaller houses during the tight-community zeitgeist. Few knew that Waddy was from New York and that his father worked for Goldman Sachs.

Waddy purchased a new 10-passenger Thiokol Trackmaster to transport his paying guests by reservation either from the Sundeck or from a pickup point on Castle Creek Road. They also cut a trail on the shoulder of Hurricane Ridge, just south of Little Annie on an exposure where the powder snow lasted longer, the Times’ article reported.

A field phone on a post at a pickup point near the Sundeck provided a 1960s-era telecommunications link to the lower warming hut, where “hutmaster Bob Sullivan — chief cook, bottle washer and radio operator — is in contact via shortwave radio, using call letters KCT719, with the mobile Trackmaster,” the Times wrote.

Preliminary ideas called for a lift from the basin to the saddle between Little Annie and Hurricane, along with a lodge and restaurant at the upper end of the lift terminal. But this simple infrastructure would go on to be mapped out into a much larger complex, cobbling together over 1,000 acres of private holdings and leased properties.

The discovered blueprints

In an ambitious plan that would make the mouths of today’s developers water, Catchings and Benedict wanted to build Little Annie basin into a beehive of activity. They mapped out a destination village inspired by Lake Tahoe’s Sugar Bowl ski area, with up to 160 phased-in housing lots and a “spectacular hotel-restaurant site set in the bowl,” all serviced by a full variety of shops — including a general store — to make the complex independent of Aspen.

The only way in or out during the winter other than skiing was via the aerial-bus gondola. Full vehicular access on new neighborhood roads would be open during the summer. This early car-free-town-in-winter concept depended on the county plowing Castle Creek Road and a busing system to and from Aspen. In Benedict’s prologue to the Annie plan, he characterized the era: “The general market conditions in Aspen and vicinity are favorable toward considering expansion of ski area facilities and additional homesites.”

He outlined one-half and one-acre lots, with two-acre lots for summer cabins in the darker Midnight Mine area to be acquired in a future phase. The majority, however, would be clustered around the village in the Annie bowl, but some might be as high as 10,500 feet in elevation near the Annie/Richmond ridge. He compared this high-altitude livability to Leadville.

In winter, snowcats would be stationed for emergencies, along with jumbo four-wheel-drive vehicles. Public and private sleighs would ferry people throughout the village. The aerial bus, consisting of up to two heated, “self-powered 25-person cabins” capable of 15 mph along a monocable, would make stops along the route from the lower parking lot, through the residential development and into the base village, each stop within a three-block walking distance.

The clustering scheme would make utility installation economical. Water could be pumped uphill from the Midnight Mine northwest of the complex to large holding tanks on Richmond Hill to gravity-feed the whole operation below.

Lifts and ski terrain

Benedict’s drawings locate six chairlifts accessorizing the aerial bus — four on the western Annie side and two on the eastern side of Richmond Hill. They anticipated building the lift-1 aerial bus first along with lift-2 running from the village gondola terminus to the top of Richmond Hill, followed by lift-3 running 1,480 vertical feet deep into McFarlane’s gulch on the east side.

Phase two lined out four more chairlifts, including one originating near the lower Castle Creek parking lot that accessed 2,000 vertical feet of northwest-facing Hurricane Gulch just south of the village.

Three more lifts would triangulate to an apex on top of Richmond Hill less than a half-mile from Aspen Mountain’s sundeck. A short lift connected the basin village to this peak. The other two serviced Queens Gulch into the northwest-facing Midnight Mine area and today’s Harris’ Wall area on the Difficult Creek side. Thus, seven lifts in all.

However, an updated 1966 submission for a feasibility study found on coloradoskihistory.com shows a re-juggling of lift alignments, with three more lifts. The most notable change was a lift that serviced an eastside Highway 82 parking lot on the Jim Smith North Star Ranch — now the North Star Nature Preserve — thus offering a way up from both sides of Richmond Hill.

Benedict’s written narrative with the plan concludes that the major selling point for the Annie ski area is “wide-open skiing, coupled with a residential ski-through area located in the heart of the slopes with a village cluster of accommodations and shops.”

Plan endorsed

In spite of access issues and the high cost of the development, former district ranger Hauk’s 1994 summation states that he “recommended approval and issuance of a permit after specified requirements were met.”

Adding fuel to approval, a 1966 Aspen Area General Plan chock full of perceptive future parking solutions, belonging to the Davis Horn local planning office, shows an area map of all ski lifts at Aspen’s then-existent ski areas. The plan also prominently included all nine ski lifts that mirrored Catching’s final 1966 submission.

But the LADC was unable to interest enough major investors, wrote Hauk, or obtain adequate financing between 1967 and 1971, when they “finally called it quits and the case was closed by the Forest Service in October, 1972.”

Enter Dave Farny

While recently sitting on the back deck of his ranch-style house in Fruita, gazing at the buttes on the horizon, Farny said, “I felt that by reimagining the Little Annie ski area we could keep the many little lodges going in Aspen and slow sprawling growth by invigorating the town itself with a new pedestrian-served ski area right from town. People wouldn’t have to travel two hours from Aspen to the top of Snowmass for wide-open, intermediate skiing.”

Farny had taken a break from burning the water ditches behind his house. Now in his eighties, he reflected on the early days, when “Aspen was a little gem populated by 10th Mountain Division vets and sincere, interesting people who cared for one another.” He wanted to show that he could build a good ski area not based on real estate sales, but designed to deliver great terrain.

So in 1974, Farny, an Aspen ski instructor, laundromat owner and operator of a mountaineering school in Ashcroft, jumped into his dream.

“For $400,000,” he said, “I bought out Waddy’s 880 acres of assembled mining claims.”

From there, he put together Forest Service leases and negotiated with adjoining land owners to combine what he estimates was 1,500 acres for the project.

In 1975, Farny presented his proposal to the Forest Service, along with a preliminary development plan prepared by Sno-Engineering planners, with access from the Smith North Star Ranch via chairlift. Though Farny’s final plan moved the base to its in-town location on Ute Avenue, he said he had a handshake deal with Smith to put a lift on his property at a later date after the town gondola was built.

This led to more meetings, studies, pro-and-con controversies, etc., involving all segments of the Aspen and Pitkin County population, which sparked a special county vote Nov. 7, 1979. Growth-conscious voters approved the project only in concept by a tally of 2,188 to 1,460, according to a February 1979 Ski Magazine article. This allowed Farny to move to site-specific review.

Amidst the hullabaloo that factionalized the town, in August of 1981 the White River National Forest approved a special-use permit for the proposed development, based upon Farny’s book-thick environmental impact statement, now on file at the Aspen Historical Society. Next, the rubber had to meet the road.

Heated times

Since the 1960s, a growing bloc of Aspen-area residents have tried to hold back free-for-all development, as shape-shifting vested interests — often from out of town — profited while trumpeting economic viability.

These factions wrestled fiercely in the 1980s and a sleepier Aspen accelerated, igniting the downvalley diaspora of in-town locals who couldn’t afford housing. At the same time, many threw up their hands, cashed in their houses and fled, considering the issue of community versus commodity.

At the same time, a heated dispute over local skiing rights dovetailed with the tensions in 1976 when the Aspen Skiing Corporation suspended the season ski pass for Aspen Mountain, because, company officials maintained, rowdy locals were driving away ticket-buying tourists. This prompted appeals to the Forest Service and even a phoned-in bomb threat —a bluff that DRC Brown, SkiCorp president, called, spinning the lifts anyway.

As a result, duct-taped locals flocked to the cheaper, then-separate Aspen Highlands pass. Full SkiCorp passes were valid only on Buttermilk and Snowmass. In 1980 local pass holders could again ski Aspen Mountain, with a surcharge sticker for an extra $10 each day on top of the $300 cost of the pass. The surcharge and pass costs ratcheted up yearly until 1991, when a full three-mountain pass was reinstated at $1,600 a pop, which in 2019 dollars comes to $3,004.

Thus, a large part of the Little Annie appeal came with Farny’s promise to bring back an affordable ski pass for locals, resulting in an odd splintering between local skiers and the anti-development crowd, who were normally in the same boat. In this environment, Farny, a skier at heart, pushed to overcome many obstacles, hoping to open for the 1983-84 season.

Same terrain, different lifts

The real doozy of Farny’s plan was the prototype gondola to be built by the edgy Italian firm Nuovo Agudio. The six-passenger cabins, of what was touted to be the most advanced and fastest ski lift in the world, were to be fashioned in a “Maserati style,” said former planner Bill Kane. A subsequent preliminary plat and unit submission to the county shows that the projected base area complex on Ute Avenue would include 69 employee housing units on site.

A Sept. 20, 1981, Denver Post article describes the single-cable system on low-profile towers angling up the east-facing side of Aspen Mountain to Richmond Hill as being built in three sections, each powered by separate electric motors with a dramatic right turn on a 10,000-foot bench, before reaching the 11,300-foot summit. This costly dog-leg section (below Harris’ Wall) was designed to go around the Loushin family’s property rather than over it.

At $11 million ($32 million today), the gondola was the most expensive item in Farny’s budget, with an estimated $30 million ($87 million today) investment for the entire project, the Post wrote.

And of course evacuation of the great machine was a center-stage concern for every deliberative body that looked at the plans. Farny maintained that a close-to-ground contour made that challenge surmountable.

The 2,250 skiers-per-hour gondola would feed one chairlift in the Little Annie basin and four on the eastside of Richmond, serving an area from the southern edge of today’s Pandora’s expansion out past McFarlane’s. The gondola ride time would clock in at 28 minutes, stocking the 4,500-skier capacity of the total ski area.

Unlike Catching’s earlier proposal that was real-estate centric, Farny’s vision placed a 1,200-seat restaurant and lodge, facility shops and additional employee housing at the top of Richmond, without a real estate scheme in the plan.

Many said this was unrealistic, yet Farny believed building a new ski area in a time of projected rising Colorado skier traffic into the 1990s would work. He remained all-in and attempted to brainstorm every concern as it arose, even in the face of 18 percent interest rates during the “stagflation” era through the 1977-81 Carter presidency.

The major hurdle remained: financing. Could income from lift tickets turn a profit soon enough to recoup the $30 million investment? And with memories of the catastrophic 1976 failure of the Lionshead gondola at Vail and the shutting down for the 1979-80 season of the sole back-bowl lift there because of a frayed cable, prospective investors took pause.

The potential ski area that straddled the north-south Richmond Hill ridge with trails into four bowls on the east and two on the west rehashed an ongoing contention about how the sun exposure couldn’t keep snow. Farny countered that the rising and setting sun arcing over the area would offer better light, a longer day of skiing and great spring corn snow.

Also, the question of skier traffic demand remained in dispute. Skier use was increasing then at 8 percent statewide, but the Aspen area had stalled at less than 1 percent, according to the Denver Post. So how could the projected 4,500 skier-capacity-resort attract enough skiers by the time the lifts started turning?

Coupled with that, more car traffic in town and an overflow of skiers that might leak out onto upper Aspen Mountain without ski tickets raised concerns. The specter of overcrowding in the Spar and Copper runs on Aspen Mountain at the end of the day if Annie skiers chose that route down instead of riding the Annie gondola to the base troubled the Aspen Skiing Corporation.

Disposal of waste water from the summit facilities was another puzzle for Farny. Showing resolve, his team hatched an innovative but untested plan to build a system wherein “treated effluent would be sprayed on the slopes as man-made snow in the winter and irrigation water in summer,” the Post reported. Doubters had a field day with that.

As for the water supply, Farny said he brought a dowser to the top of Richmond Hill who used a forked stick to find water and then hand-held brass rods to find depth. The water witch predicted water 190 feet down. They drilled and hit a 50-gallon-per-minute well at 194 feet, Farny said, enough to fill a reservoir to supply the entire project.

All these obstacles needed to be specifically solved. So Farny, backed by his Little Annie Limited Partnership, which included such town notables as Bil Dunaway, Fritz Benedict, Charlie Patterson, Jim Otis and Jack Nicholson, set to task. Numerous enthusiastic local small investors anted up as well. At the same time, John Denver was a Little Annie booster but not an investor.

Realities strike home

With the Forest Service EIS approval in hand, Farny’s team worked with Pitkin County planning and zoning, which tabled any decisions until he came back with remedies to their concerns — of which the former is just a partial list — before county commissioners would even take up the proposal.

Farny recollected how when the 18 percent interest rates caused investors to balk, he turned to the Les Arcs skiing company in France for financing. They wanted to expand into a U.S. ski area in Aspen, he said. However, just-elected French socialist President Francois Mitterrand’s government instituted capital export controls, putting a halt to French money fleeing to other countries, only to be reversed a few years later — too late for Farny — after currency traders hammered the franc.

In the end, like Catchings’ dream, Farny fell short of financing and was unable to come back to P&Z with his completed punch list. He recounts how he went so far as to sell his West End family home to keep the project afloat while the stewing Les Arc financing remained in play, right up until the sudden financial snafu froze French capital.

Dinged by the town controversy and with so much skin in the game, Farny arrived at a financial cul-de-sac. In 1983 he and his family abruptly left Aspen and moved to the stunning Skyline Ranch in Telluride, a one-of-a-kind property he had bought in 1969 at a “great deal for only $10,000 down.” There he started a mountaineering school before he and his family converted the spread into a successful and well-known dude ranch.

Basin goes on

Though no Little Annie ski area ever got off the ground, district ranger Hauk characterized the high-use area in 1994 as a “battleground for two snowcat powder tour operations, snowmobilers and back country skiers, complicated by intermingled private land and mining claims.” Some say the situation is the same today.

Pete Stouffer, a resident of Little Annie and long-time caretaker of an off-the-grid house also once owned by Catchings, said “the place was a quiet, happy hippy village without any motorized equipment back in Waddy’s day”— though the era predated Stouffer.

Anecdotal legend holds that Ken Kesey’s famous Merry Pranksters, chronicled in Tom Wolfe’s book “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test,” drove the famous psychedelic “Further” bus up Little Annie road in the 1960s and spent a stretch of summer there.

These days, Stouffer said, the basin is noisy at all hours, with road traffic and constant ATVs, snowmobiles and now the new scourge — little brothers of the snowmobile, which are the motorcycle snow bikes with a rear-paddle tread and a ski in front that can go anywhere.

Under a new custodian

Today the majority land holder in Little Annie basin is John Miller, a former dairy products distributor from Indiana now in his eighties, whose Castle Creek investors group formed when Miller bought out Farny’s holdings in a bankruptcy auction in 1982. Miller recalled that the auction was actually held on the Pitkin County courthouse steps and that only one other bidder showed up.

Initially, Miller said, he thought he might back Farny’s efforts to build a ski area, but after Farny decamped, “I grew to appreciate the area as it was.” Miller built himself a packaged cabin, shipped over by boat from Finland. Along with the kit, a pair of Finns arrived and erected his 1,000-square-foot cabin to face Mount Hayden.

Miller has parceled out some property to longtime cabin dwellers in the basin and characterizes himself as a custodian of the property there. What his minority holding partners or his heirs may try to do in the future is unknown.

Whether Little Annie will remain a side-country recreation ground populated by low-key cabin dwellers and a few down-sized trophy homes or morph into the next Red Mountain, remains to be seen. But as of now, rural and remote zoning passed in 1994 restricts home sizes to 1,000 square feet and serves as an effective rural buffer between booming Aspen and an endangered way of life.

Tim Cooney is an Aspen-based freelance writer, a former Aspen Mountain ski patroller and a current summer ranger there. He writes about Aspen history for Aspen Journalism, a nonprofit organization that supports in-depth reporting in the public interest, in collaboration with the Aspen Daily News. The Aspen Daily News published this story on Sunday, April 28, 2019.